Study reveals iOS privacy labels miss the mark

By Ryan Noone

For more than a decade, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) have been working to pioneer privacy nutrition labels, advocating for a quick and easy way to show tech users how their data is being collected and used. Recently, companies like Apple and Google have begun requiring app developers to disclose this type of information in an effort to provide consumers with the knowledge necessary to make educated decisions. However, with difficult-to-find labels packed with confusing technical jargon, experts at CMU’s CyLab Security and Privacy Institute have found their current approach is missing the mark.

“Traditional privacy policies are long and contain a lot of legalese, making them difficult to understand,” says Shikun Zhang, a Ph.D. student in the Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science’s (SCS) Language and Technologies Institute (LTI). “Additionally, if users read through every privacy policy they encountered, it would take a significant amount of time.”

“The concept of privacy nutrition labels aims to standardize and summarize this information into something users can easily digest.”

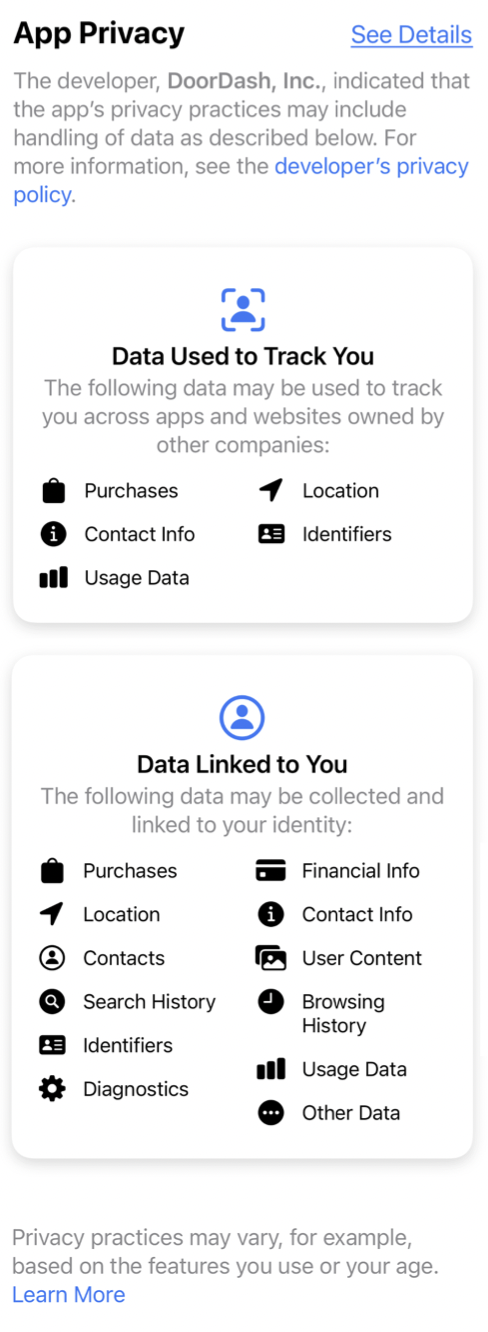

In a recent study, Zhang interviewed 24 lay iPhone users to investigate their awareness, understanding, and perceptions of Apple’s privacy labels. Participants were asked to review the information provided by two food delivery apps and offer feedback about how they interpreted their disclosures.

While the study’s participants largely agreed on the importance of making this information available to users, the findings reveal significant misconceptions and general difficulty in understanding what the IOS privacy labels, in their current form, are really saying.

“There are a number of reasons why people are having trouble understanding these,” says Lorrie Cranor, CyLab director, and professor in CMU Engineering’s Department of Engineering and Public Policy and SCS’s Institute for Software Research.

“One is that the terminology is confusing. Apple uses words like ‘tracking,’ and people make assumptions about what that means based on everyday life. However, that definition typically doesn’t match what Apple means when it says tracking.”

Cranor also says users assume that if a privacy label doesn’t mention a specific data type, it isn’t being collected; however, companies are allowed to omit certain information from these labels if they meet requirements in the fine print.

A lack of awareness of the labels’ existence is another major issue.

“Currently, privacy labels are listed so far down in the app descriptions that users rarely scroll far enough to notice them,” says Norman Sadeh, co-director of CMU’s Privacy Engineering Program and head of the Usable Privacy Policy Project. “As a result, few participants reported being aware of their existence, let alone using them when deciding whether to download an app on their phone.”

Sadeh adds that because the labels are only accessible in the app store, users do not benefit from the information they contain when managing other aspects of their privacy, such as controlling the privacy settings (or “permissions”) that determine what sensitive information each app can access.

In order to improve Apple’s iOS privacy nutrition labels, the study’s authors suggest implementing an easier-to-understand design making definitions and contextualized examples of the data collected more accessible, and embedding actions and controls that allow users to manage their privacy settings.